Induced and Parasitic Drag

Part I. Induced Drag

In aviation, induced drag is a phenomenon where moving objects that redirect airflow (an example being F1 cars’ wings) create aerodynamic drag as a side-effect of generating lift or downforce. In F1 cars, this effect is most apparent at the wings, which are the components that generate the most downforce.

As this diagram shows, induced drag is a side-effect of lift or downforce being generated perpendicular to the effective airflow, thereby creating a horizontal component of effective lift opposite to the direction of travel. This creates an aerodynamic drag force known as “induced drag” or “lift-induced drag”.

Unlike parasitic drag, induced drag cannot be reduced through streamlining or using smoother materials: Whenever any lift or downforce is generated, induced drag will be generated. However, it can be reduced through changes to the factors of the aerodynamic features. The effect of induced drag is governed by the equation $D_i=\frac{L^2}{\frac 1 2 \rho_0 V^2_E \pi b^2}$, where $D_i$ is induced drag, $L$ is lift/downforce, $\rho_0$ is the air density, $V_E$ is equivalent airspeed, and $b$ is the wingspan. Clearly, it is inversely proportional to $V_E^2$ and directly proportional to $L^2$, which means that induced drag is reduced as cars get faster and have larger wingspans. Obviously, according to regulations, larger wingspans are infeasible, however, Formula One cars usually travel at such high speeds that induced drag does not dominate over parasitic drag.

Part II: Parasitic Drag

Parasitic drag is likely the “air resistance” that most F1 fans, drivers and engineers alike are most familiar with. At the high speeds seen in Formula One racing, parasitic drag becomes an important factor. While there is no single equation governing parasitic drag (unless you can solve the Navier-Stokes equation generally, in which case, go collect your million dollars :P), parasitic drag can be roughly categorised into two forms: Skin drag and Form drag.

Skin Drag

Skin drag is governed by the equation $F=\int C_f \frac{\rho v^2}{2}dA$ where $C_f$ is the skin friction coefficient, $\rho$ is the fluid density, $v$ is the effective airspeed of the vehicle, and $A$ is the surface area of the vehicle. Put simply, skin drag is the effective friction between the air and the body of the car, and changes based on the fluid the body is moving in and the surface used to create the body of the car.

Form Drag

Form drag, on the other hand, is influenced by the shape of the object. Form drag is generally calculated by experimental design and taking the empirical value of the drag coefficient $c_d$ through wind-tunnel calculations. Although slightly difficult to quantify, the effects and how to lessen them are well known: Form drag can reduced through streamlining, allowing air to pass over the surface in a more laminar manner without inducing vortices, which create further form drag. Reducing form drag is important not just to Formula One, but to other applications like high-speed rail rolling stock design, in order to maximise efficiency and speed.

Overall

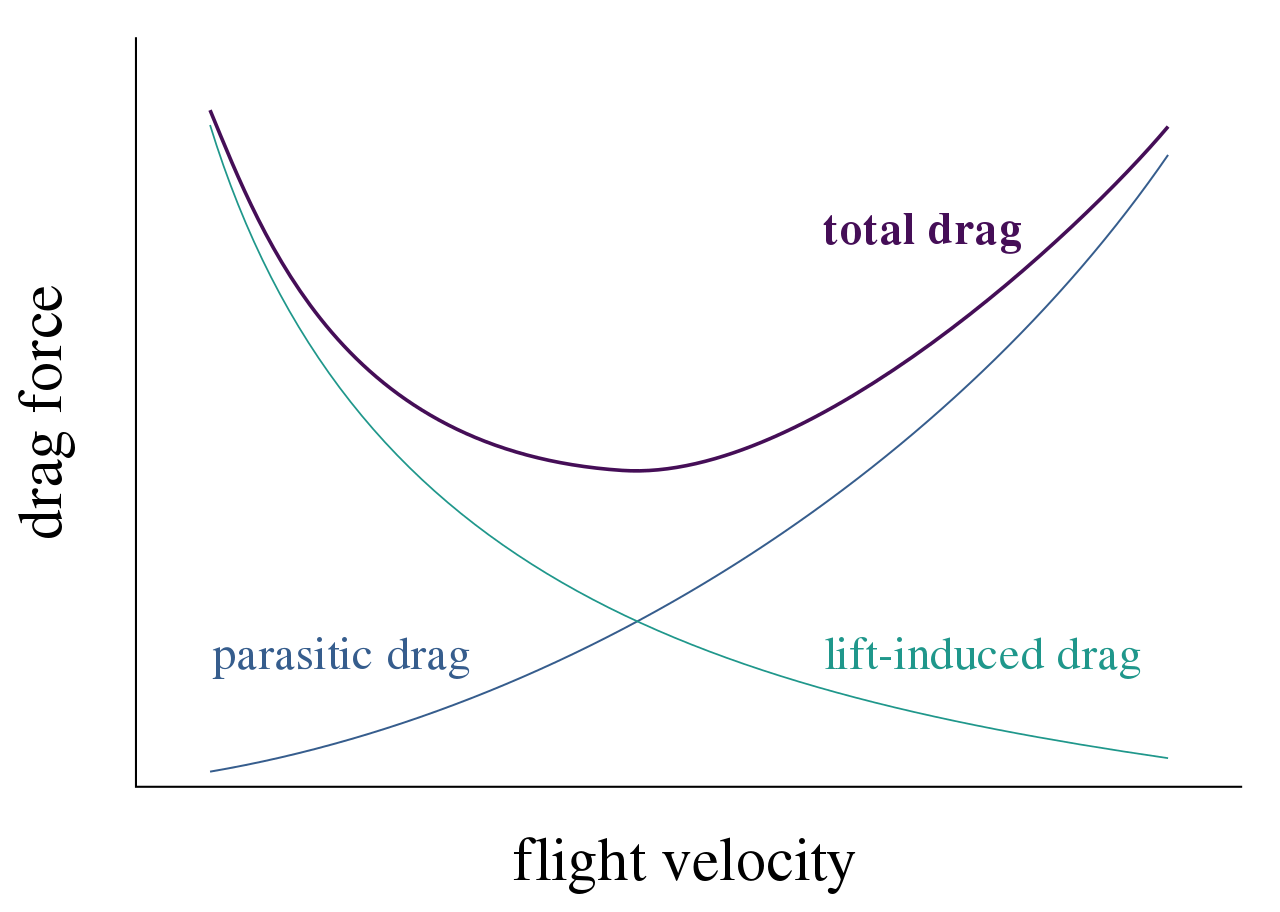

Total drag can be found from the addition of parasitic drag and induced drag. Since parasitic drag generally increases with velocity while induced drag generally decreases with velocity, the graph of drag against velocity looks somewhat like this:

Since F1 cars’ speed is somewhere around the center of the curve, both parasitic drag and induced

drag have approximately equal influence on the total aerodynamic drag, so optimising both is important.

Image Sources:

-

By Johnwalton, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18849041, modified

-

Own work (Wang Hengyue)

-

By Olivier Cleynen, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51974460